Muse Air was incorporated in January 1980 by Michael Muse, the former Chief Financial Officer at Southwest Airlines.

In October of that year, Michael Muse assumed the position of President and Chief Operating Officer of the new company and his father, Lamar, was named Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer. Lamar Muse had previously served as President of Southwest Airlines from 1971 until 1978.

The formation of Muse Air Corporation was formally announced at a press conference in Houston on October 27, 1980.

“Cut-Rate Fares and Hot Pants”

(Time Magazine – November 17, 1980) Lamar Muse, 60, the Texan who made upstart Southwest Airlines one of the nation’s highest-flying carriers by slashing fares and ballyhooing it as the “love airline,” will soon be back in the air after a two-year grounding. Muse Air will take off next June for seven destinations from San Antonio to Memphis. By 1985 the new airline will fly to 24 cities, including Atlanta and Pittsburgh.

Aggressive promotion and price cutting have long been Muse’s trademarks. As Southwest’s first president, he started flights in 1971 that gave new meaning to the term friendly skies. The airline billed itself “The Somebody Else Up There Who Loves You.” Upon boarding a flight, passengers were greeted by a soft, sexy voice, saying: “Hi. I’m Suzanne. Y’all buckle your seat belts and don’t dare get up. We don’t want anything happening to you now because we love you.” The stewardesses, personally selected by Muse himself, sported tight hot pants and leather go-go boots. In-flight drinks were known as “love potions,” and cash registers that issued tickets were “love machines.”

Such pizazz impressed good-ole-boy Texans, who were soon vying for aisle seats where stewardess viewing was best. Southwest flights were also packed because of the low fares. A nighttime or weekend trip from Houston to Dallas was only $13 on Southwest, compared with $26 on competing Braniff and Texas International. Soon the inexpensive and colorful Southwest flights within Texas were as much a part of local tradition as the Alamo, longhorn cattle and the Dallas Cowboys.

In 1978, however, Muse and Southwest had a falling out. Muse wanted to expand by starting up operations at Chicago’s Midway Airport, but Southwest’s board of directors balked because it considered the strategy too expensive and risky. Muse thereupon quit. But in the past two years he has made plans to raise $32 million for Muse Air, of which he will be chairman. Says he defiantly: “This time I’m not going to get caught between a bunch of knuckleheads who don’t know their asses from first base.”

Muse Air is another of the cut-rate airlines spawned by deregulation of the industry. Next month, New York Air, a new subsidiary of Texas International, will start providing 18 flights a day along the New York City to Washington, D.C., corridor in direct competition with the busy Eastern Air Lines shuttle. And People Express next year will begin service to six cities out of Newark.

Since New York Air had trouble obtaining scarce landing rights at Washington’s National Airport, Muse decided to fly his carrier into Tulsa, St. Louis and other less congested Midwestern and Southern cities. Says he: “Our target is where big airlines have cut back, the heartland of Middle America.” The new airline will fly fuel-efficient DC-9 Super 80s, and Muse says that he will slash prices by up to 66%. Fares will be low enough to “get people off the interstate highways and onto airplanes.” And what about stewardess outfits? A slight smirk ripples through Muse’s white mustache as he says: “They won’t look like World War II nurses’ uniforms.”

1981

“New Airline Battle in Texas”

(William K. Stevens, The New York Times – July 8, 1981) The battle that is about to begin in the skies of Texas probably will not be as bitter as the tough, mean slugging matches that took place between the state’s airlines during the 1970’s. But it ought to be a lot more fun, based as it partly on style and sex appeal.

A decade ago, Braniff International and Texas International Airlines, then the big boys on the block, nearly knocked out little Southwest Airlines, their sassy new low-fare, frequent-trip intrastate rival, before the fight was fairly started.

As it celebrates its 10th anniversary this summer, Southwest has not only survived its competitors’ lawsuits and price cutting, but has also triumphed. That success has attracted new competition, and Southwest, a leader among the growing group of cut-rate regional carriers, is itself being challenged by a new upstart Texas airline – Muse Air.

Ironically, Muse Air is the creation of Lamar Muse, the colorful and blunt entrepreneur who built much of Southwest’s success before being forced out as its president in 1978 by what he says was an internal power play on his part that went awry. Now 61 years old, with white hair and a mustache to match, Mr. Muse has come out of retirement to start, along with his son, Michael, the new Dallas-based carrier.

Muse Air is scheduled to make its first flight on July 15, and the battle with Southwest promises to be a study in hard-nosed business competition. For Muse Air is challenging Southwest head-to-head on its major route: Love Field in Dallas to Hobby Airport in Houston and back, one of the most lucrative routes in urban America. Mr. Muse hopes to beat Southwest at its own game, a game he helped to invent, at least well enough for Muse Air to show a profit in its first quarter of operation.

”I hate like hell to compete with them,” Mr. Muse said in an interview. ”It’s going to be misery, because they’re tough. But, God Almighty, I just could not resist Love Field-to-Hobby – 1,250,000 passengers a year carried by one carrier,” he said, in reference to Southwest. ”It’s the only major airline monopoly in the world.”

As an advertising and public relations spectacle, the Muse-Southwest battle also promises a lot. The cream-colored planes with the elegantly dashing ”Muse Air” signature splashed across the body in blue script are designed to counter Southwest’s hot gold, red and orange craft. In addition, Muse is ready to offer what it considers style and sophistication against Southwest’s patented, informal, we-love-you approach based frankly on sex appeal, and to match its flight attendants’ Gucci pumps, slit skirts and sleeveless jackets against Southwest’s boots, hot pants and jeans.

On top of all that, Mr. Muse plans to appeal to the sensibilities of the 1980’s by becoming the first airline to ban smoking aboard flights entirely.

The Muses – Lamar as chairman and Michael as president – are starting their airline with a capitalization of $38 million, most of it raised in a public offering. They are doing so in a state that, along with California, was a testing place for cut-rate fares in a deregulatory setting.

Muse Air’s fares will exactly match Southwest’s tariffs of $25 and $40, one way, depending on time of day, on the 240-mile, 50-minute run between Dallas and Houston.

“Big Daddy is Back”

(Dan Carmichael, UPI – July 9, 1981) Texan’s “fed up” with the “sexist” advertising and promotion campaigns of Southwest Airlines are welcome to try the new Muse Air, says Lamar “Big Daddy” Muse, the man who started Southwest 10 years ago.

“This is the second time around,” the feisty Muse said Wednesday, adding he was excited at the prospect of taking on Southwest, one of the nation’s most successful regional carriers.

“We will be pleased to have as many people as possible as passengers who have become fed up with Southwest and that (sexist) image that they’ve really tried to push in the last few years. We’ll take all the passengers and support we can get,” he said.

Muse said he has male and female flight attendants – all attired in a “classy” manner. The women will be dressed in navy blue and camel brown, their skirts featuring a 13-inch slit on the right side and sleeveless jackets with a flounce at the waist. The men will wear navy blue slacks, brown traditional blazers, and button-down shirts and ties.

Muse got considerable attention several weeks ago when he became the first in the nation to announce that all seats on his airline would be “no-smoking.” He said the response to his move had been “unbelievable” and only two people had written in opposition.

Muse has taken out several full page ads in Texas newspapers declaring: “Big Daddy is Back.”

Muse said he had no contact with any officials at Southwest, but said the airline’s officials were not “ignoring” his activities.

Despite his challenge, Muse said Southwest is “one of the most profitable companies in the world and will continue to be.”

Muse started Southwest a decade ago, but left in 1978 in the midst of an executive policy dispute over further expansion. He was prohibited from engaging in direct competition with Southwest for two years.

Flights between Dallas’s Love Field and Houston’s Hobby Airport begin July 15, with inaugural flights taking off simultaneously from both airports. The jets are cream-colored with “Muse Air” emblazoned in large blue script on their sides and tails.

Photo source: Barry Canning via Museair.com

Photo source: Submitted by Barry Canning via Museair.com

Photo source: Submitted by Barry Canning via Museair.com

Muse Air began operations on July 15, 1981 with a fleet of two McDonnell Douglas MD-81 aircraft named “Spirit of Dallas” and “Spirit of Houston.”

The inauguration of service included ribbon-cutting ceremonies which took place at 7:00am at Dallas Love Field’s gate 6 and Houston Hobby Airport’s gate 18.

The company’s initial flight schedule consisted of thirteen roundtrip flights between Dallas Love Field and Houston Hobby Airport during the week with decreased frequency on weekends. Ticket prices between Dallas and Houston were $40 for “Prime Time” flight and $20 for “Leisure Time” flights.

Muse Air’s inauguration of service also marked the first McDonnell Douglas MD-80 service in the state of Texas.

One of Muse Air’s first aircraft, N10029, “Spirit of Houston,” is shown at Love Field on May 16, 1982.

This aircraft, as well as its sister aircraft, N10028, “Spirit of Dallas,” were initially built for Austral Líneas Aéreas of Argentina. When Austral decided not to take delivery of the aircraft, they ended up with Muse Air and entered service still outfitted with Austral’s cabin interiors.

Although a number of small commuter airlines in the United States had banned smoking, Muse Air’s no-smoking policy was considered revolutionary when the airline launched operations.

Photo credit: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum archives via Museair.com

“Muse Air Company Launches First Flight”

(Associated Press – July 16, 1981) Lamar Muse’s latest venture has gotten off the ground, and once again the sky’s the limit. He has another airline company.

Muse, the president of Southwest Airlines who was ousted in a power struggle in 1978, took off Wednesday on the maiden flight of Muse Air Corp., of which he is chairman and chief executive officer.

“Southwest made me a helluva lot of money and I’m grateful to them for that, no matter what else happened,” Muse said. “Now we have to beat them, and it won’t be easy.”

Passengers waiting for Muse’s sold-out 7:20am flight from Dallas to Houston were treated to champagne bubbling from a fountain and music pouring from the strings of two violinists and a classical guitarist.

As they boarded, they were not reminded to “Extinguish all smoking materials” because the plane – one of two Muse Air crafts – is smokeless. There is no smoking, period, on the Muse line.

“I hope no one had a nicotine fit,” Muse said at the end of the 50-minute flight.

He’s starting small, but with a good base.

Muse Air sold $37.5 million worth of common stock last March, and got a $57 million line of credit with banks in Dallas and Chicago.

Should he find himself short of cash next year, McDonnell Douglas has volunteered $17 million in credit to help him buy four new Super 80s.

Muse, who has $9 million in working capital, says he can last 17 weeks even if he doesn’t make a penny. To break even, the company’s 28 weekday flights and 34 weekend runs would have to be an average of 49 percent full.

“We know there will be some lonely planes at first,” he said. “That will give our crews plenty of time to learn how to provide service.”

Muse Air has a 20-minute turnaround time set for its shuttling planes, and some industry watchers wonder whether the crews can pull it off.

“They probably will fall behind at first,” he said. “We hope they will get better as we go along.”

A Muse Air ticket to Houston is $40 regular, $25 for early morning and late evening – the same price charged by Southwest Airlines.

“I hope to hell they don’t cut the fares on me,” Muse said. “Southwest will be tougher than horseradish to compete with.”

The company has authority to serve 24 cities, including eight in Texas, as well as such markets as Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit and Atlanta. But Muse Air flies out of Dallas’ Love Field airport, and federal regulations forbid Love-based companies from going anywhere but Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, Oklahoma and New Mexico.

He said he will work to repeal the Love Field law, which he calls “a piece of revenge on Dallas by somebody from Fort Worth.”

The bill’s sponsor was U.S. Rep. Jim Wright, D-Fort Worth, the House majority leader.

Just 19 days after Muse Air began flying, the Air Traffic Controllers in the United States went on strike beginning August 3, 1981. Restrictions on where and when airlines could operate were put into place and Muse Air’s growth plans were immediately curtailed.

Muse Air’s September 9, 1981 flight schedule is shown above.

“Shaky Takeoff”

(Paul Burka, Texas Monthly – October 1981) Muse Air, former Southwest Airlines president Lamar Muse’s challenge to his old employers, hasn’t really gotten off the ground yet. You’ll recall that Muse Air, which flies the Dallas-Houston route exclusively, has presented itself to the public as a more elegant version of Southwest: it features reserved seating, no smoking, conservatively dressed flight attendants, chic white planes, and newspaper ads portraying Muse as a distinguished “Big Daddy.” The airline got off to a slow start because the air traffic controllers’ strike hit two weeks after it began operations, and by mid-September, its “load factor” – the crucial number in the airline business, the percentage of seats filled by paying customers – was just 31 per cent; the break-even point is 48 per cent. Muse insists that things are getting better and that he sees the light at the end of the tunnel, and he’s going to stick with his idea, except for one thing. “We’re phasing out this Big Daddy crap,” he says. “Hell, I never did like it in the first place.”

“No-Smoke Airline”

(Nigel Moll, Flying Magazine “Reporting Points” – October 1981) Muse Air is not allowing smoking in any section of its DC-9-80s flying between Dallas Love Field and Houston Hobby. Company research shows that for every passenger who asks for a seat in s smoking section, five request the non-smoking section. Founder Lamar Muse also says that a significant number of smokers prefer to forgo smoking on such short flights – 50 minutes, in the case of Dallas-Houston. Muse realizes that confirmed smokers will book with other carriers, “but for every one of them, we believe there are 10 travelers who will make the switch to Muse Air for, if no other reason, our no-smoking policy. In any event, it will not take long to find out.”

… speaking of which. Before having the side’s of Muse Air’s airliners painted with the company logo, chairman Lamar Muse took an unusual precaution. The logo is a signature and, according to a report in the Wall Street Journal, Muse Air didn’t want the competition taking the scrawl to be analyzed and finding it was the work of a demon or maniac. Muse, therefore, beat them to the punch and hired Ray Walker, of Universal Mind Spa, Dallas, to perform an analysis. His conclusions: “The backstroke on the beginning letter ‘M’ indicates that this person examines past experiences and goes a short distance into the past and then sweeps forward with strength. Since the large ‘A’ is an indication of pride, we know that there is a great deal of pride. The dot over the small ‘i’ is very close to the stem; this means there is a good memory and… close attention to details. Since it is pretty much a dot, this is a sign of loyalty.” Walker also detected a tendency to put “the break on doing things impulsively, and this is shown by the long bar at the end of the signature.”

Muse Air’s proposed route map as of October 1981. The airline’s Civil Aeronautics certificate gave it authority to serve 24 cities in 13 states.

“Muse Air Founder Competes Against His Own Creation With an Aura of Success.”

“The man who wrote the book on making profits now hangs a ‘No Smoking’ sign in the ‘largest monopoly market in the world.'”

(Danna K. Henderson, Air Transport World – October 1981) In the summer of 1971, veteran airline executive Lamar Muse wrote the rulebook for making money in the airline business.

By creating a new operation with inherently low costs, eliminating such “frills” as interlining, and dressing up the product with a little pizzaz, he postulated, an airline could slash fares in half, offer high frequencies, and thereby woo people away from their automobiles for trips of 200 or 300 miles. Muse put his formula into place at Southwest Airlines, and the result has been one of the most financially successful carriers in the industry’s history – and one which provided much of the impetus for deregulation in the U.S.

In the summer of 1981, Lamar Muse took on the formidable task of reinventing the wheel and competing against himself.

As Southwest was celebrating its tenth anniversary on June 18, Muse and his 32-year-old son, Michael, were less than a month away from launching their new Muse Air Corp. on July 15 into “the largest monopoly market in the world” – the 50 minute run between close-in Love Field in Dallas and Hobby Airport in Houston. Unchallenged, Southwest has been transporting 1.25 million passengers a year on the route, and Lamar felt that its 80% load factor pointed to a shortfall in capacity. He also was aware that Dallas-Houston was the fastest growing airline market in the U.S.

MILLION-DOLLAR “BIG DADDY” CAMPAIGN

“Big Daddy is Back,” proclaimed Muse Air’s marketing salvo. The $1-million ad campaign also revealed that Big Daddy had not invented a new formula for airline success but intended instead to improve upon the old one by hitting at the few chinks in Southwest’s armor, especially its “cattle car” image.

“Sophistication” and “elegance” are words that are heard constantly by visitors to Muse Air’s temporary executive offices in a hotel near Love Field (headquarters will shift to Houston within three years). “First-class service at bargain-basement prices” is the phrase that Michael Muse uses to describe what his airline is trying to achieve.

The frankly sexy, red-and-gold “love in the sky” image that Lamar created at Southwest has been replaced at Muse Air by a cool blue-and-cream “aura of class.” A bold, dark blue, 57-ft.-long, computer-engineered “Muse Air” signature slants along the cream-colored fuselages of the carrier’s two “newest in the skies” airplanes – McDonnell Douglas DC-9-80 “comfort cruisers” outfitted with 155 roomy Fairchild-Burns Airest 2000 seats in a 3-2, single-class configuration.

The open seating plan which Muse instituted at Southwest is one of the airline’s biggest sources of passenger complaints today, so at Muse Air all seats are reserved. “You’ll never have to race anybody for a seat when you fly Muse Air,” said one ad. “Big Daddy’s not into cattle drives, so there’s no stampeding to get on the plane.” And since load factors must approach 80% before any Muse Air passengers are required to sit in a center seat, the airline presents center-seat passengers with a bottle of champagne from “Big Daddy’s private stock.” The first high-load-factor flight came in mid-August, and Michael Muse made the champagne presentation personally – and happily.

Muse Air also has lengthened the quick turnarounds for which Southwest is famous – and often criticized. “You deserve more than hurry-scurry airline service… ten-minute turnarounds with planes leaving the gate while you’re still standing in the aisle,” says one ad. “Muse Air deliberately spends 20 minutes on the ground between flights so nothing’s rushed, especially you.” Of course Muse Air is flying 14 daily roundtrips in the Love-Hobby market, versus Southwest’s 30.

The emphasis on first-class service extends down to items like embossed ticket jackets and the use of aisle carts instead of trays for inflight beverage service.

Lamar Muse’s biggest marketing coup at his new airline so far has been his institution of a strict no-smoking policy aboard all flights. Observing that the smoking sections of airplanes were shrinking rapidly, he researched the matter and found that at least four out of five passengers were requesting no-smoking seats on flights of less than an hour. Even smokers were beginning to opt for the no-smoking section. So Muse became the first no-smoking airline (except for some commuters), and passengers reaction to date has been running about 100 to 1 in favor of the policy.

Muse himself gave up smoking last February, but he does not require his employees to be non-smokers. And he admits that Muse Air may have to permit limited smoking if it moves into longer routes. But he was pleased that Muse Air’s first charter was booked by a company that selected the carrier specifically because of its no-smoking rule.

In another departure from Southwest’s practices, Muse Air has succeeded in plugging itself into the existing travel agent system in spite of the fact that it does not interline or offer joint fares. Gaining the necessary approvals was an arduous and expensive process, says controller W. James Thomson, but travel agents “are able to write tickets on Muse Air just like they do on any other airline,” and some 30% of Muse Air’s passengers already are being ticketed by travel agents. Lamar Muse thinks that Southwest made a “big mistake” by adopting a program which requires agents to buy tickets in blocks and resell them.

NO CUT-RATE FARES

There is one key element of Big Daddy’s original formula that he has not been able to adopt at Muse Air yet, and that is the cut-rate fare. Southwest’s $40 peak/$25 off-peak Love-Hobby fares are bare bones, and Muse also recognizes that, “They could kill us in a fare war. They could fly passengers on that route for nothing without a lot of effect on their bottom line.” Muse Air has contented itself with matching Southwest’s fares and offering passengers more for their money. But cut-rate fares will reappear once Muse Air expands outside Southwest’s territory.

Is Big Daddy’s comeback succeeding? When ATW visited in late August, it was too early to tell. Lamar Muse initially had projected profitability for the fourth quarter of 1981, but that was before Muse had concluded at the end of June that the air traffic controllers weren’t going to strike and decided to put its small fleet into the air just two weeks before the strike became a reality.

The “inordinate amount of adverse publicity” accorded to the strike by the media has caused prospective passengers to seek out alternatives to short-haul flights, Lamar laments, “and right now the telephone is our biggest competitor.” But he remains undaunted. “I’ve always felt that every problem was an opportunity in disguise,” he says. “I haven’t found the opportunity in the strike yet, but I will.”

Although Love and Hobby airports are not among those at which flights have been restricted by the Federal Aviation Administration, difficulties in obtaining timely clearances into the Dallas-Fort Worth area forced Muse Air to cancel 58 flights during the strike’s first week. Cancellations were down to fewer than one a day by early September, and traffic was beginning to pick up.

During the first six weeks of operation, through Aug. 31, Muse Air carried 43,299 passengers, or an average of 39.8 passengers on each of its 1,087 flights. Lamar Muse does not find the 25.7% load factor discouraging, however, pointing out that Southwest started out with a 17% load factor and did not reach its breakeven of 28 passengers per flight for three years. “In five years,” he predicts confidently, “we’ll be splitting the Love-Hobby market equally with Southwest.” Southwest, incidentally, greeted its new competitor with an ad saying, “Welcome To Our Skies,” and since then has largely ignored the upstart.

Much of Muse Air’s current confidence arises from its enviable financial position. In April, it banked $36 million as a result of a public stock offering managed by E.F. Hutton & Co., selling 2.2 million “units” (one share of common stock plus one-half warrant to purchase an additional share at $16) for $17.50 apiece. The company’s founders raised a 25% stock interest, which will be reduced to 19% if all the warrants are exercised.

Muse Air was actually founded by Michael Muse in January 1980. For several months it consisted only of Michael Muse and a secretary. In October, deciding that his semi-retired father “had been laid back long enough,” he signed Lamar Muse on as a consultant.

REVENGE BECKONS

The elder Muse admits that he was torn between his desire to continue enjoying life at his home in east Texas and his itch to “get back” at the airline which had shown him the door two years earlier.

Lamar Muse’s ascension to the presidency of Southwest in 1971 had culminated an airline career stretching back to 1948, when he joined Trans-Texas Airways (now Texas International) as chief financial officer. After stints as assistant VP-corporate planning at American Airlines and VP-finance at Southern Airways, he served as president and chief executive of Central Airlines before its merger into Frontier, and then as president and chief executive of Universal Airlines.

The early years at Southwest were exciting ones as he struggled to keep the fledging one alive while slugging it out in the courts with Braniff and Texas International, who were determined to keep the new carrier away from what they regarded as their turf. The court battles finally won, the flamboyant Muse stormed the halls of Congress as a proponent of deregulation.

By 1977, however, he was bored. Southwest, he recalls, “had become so cut-and-dried. It was so successful.”

Lamar Muse decided that the cash flow could be best used to start a Southwest-type operation out of Chicago’s Midway Airport, and Midway-Southwest was formed amid much fanfare. Muse planned to move to Chicago in the fall of 1978 to get the new venture going, and then to cut back severely on his activities when his contract came up for renegotiation in the fall of 1980. His son, who was VP-finance and administration at Southwest, would then become president of Midway-Southwest “if he had proved by then that he was capable.”

Muse’s plans were derailed by what began as a dispute in the Southwest boardrooms over the proper airplanes for the new subsidiary and escalated into a “him or me” confrontation.

“Frankly, I miscalculated,” Muse mused to ATW. “I certainly didn’t think they’d choose him instead of me.” He fully expected victory when he entered the fateful board meeting, “and I was the most surprised man in the world when I heard that the first order of business was to accept my resignation.” (Southwest did honor his contract. He was paid full salary until October 1980, and will continue to receive $50,000 a year for several more years.)

Muse was admittedly bitter, but he decided he was “too old and too rich” to fight further. He went home to east Texas and set about achieving three longstanding ambitions: to own a nice boat, to ride a motorcycle, and to drive an 18-wheeler. He acquired a luxury cruiser which he bases in Seattle, a city to which he would like to move someday. He acquired a powerful motorcycle on which he and his wife Barbara have ranged as far as Canada. And he acquired, for a short period, part interest in a milk-hauling company and did indeed drive an 18-wheeler.

Meanwhile, Michael Muse, who had been booted out the Southwest door along with his father, was plotting a return to the airline business, which he found much more interesting than the legal and accounting profession for which he had been trained.

ONLY THE DC-9-80 WOULD DO

He was thinking in terms of acquiring a small fleet of used DC-9s, but his newly hired consultant decreed that in order to be successful, a new airline had to have new airplanes – specifically DC-9 Super 80s, “I actually was enticed back into the airline business by that airplane rather than by Michael,” Lamar told ATW.

Muse Air began negotiating with McDonnell Douglas for four Super 80s for delivery in June 1982 and embarked upon what it thought would be a leisurely 18-month course of gearing up to start service. But in early 1981, McDonnell Douglas called to report that two Super 80s destined for Austral Airlines could be obtained on a year’s lease because of temporary financial problems at Austral.

After some “tough negotiations,” Muse Air entered a “very favorable” lease under which it is paying a total of $4 million for its year’s use of the two aircraft. McDonnell Douglas also is providing training for 20 pilots and 20 mechanics, and is supplying a large quantity of spares on consignment until June 1983, with Muse Air paying only for the spares that it actually uses.

Another $13.6 million from the stock sale was spent on the four DC-9-80s that will be delivered in June. The airplanes will cost a total of $88.5 million, and Muse has an option to lease them for 15 years rather than buying them. McDonnell Douglas has also agreed to $17.7 million worth of subordinated financing. The final financial arrangements will be dependent on the interest rate situation next June.

Since Muse Air has treated all of its pre-operating costs as expense items rather than capitalizing them, it entered service in July with a very attractive balance sheet and with enough cash on hand to operate for about five months with zero revenues. For the quarter ending June 30, in fact, it had a net income of $117,879, primarily from interest on short-term investments.

“Then we started flying,” laughs Michael Muse, who adds that he does not anticipate a profit in the third quarter.

BOARD EXECUTIVES TAKE A CHALLENGE

By early March, Muse Air had assembled a seven-man management team with a total of some 162 years of airline experience. With the exception of the Muses, all of the executives came directly from other airlines and they and many of Muse Air’s lower-echelon employee took salary cuts as much as 50%.

Their motives for moving to Muse included the excitement of creating a new airline, frustration in their former positions, and their expectation of future financial rewards through stock ownership and profit-sharing. The latter, says Michael Muse, will begin early next year and will be a large part of the salary structure. Employees will receive their profit shares in cash on a quarterly basis rather than having to wait until they leave company as is the case at Southwest.

Muse Air’s organizational chart is headed by Lamar Muse, 61, who holds the titles of chairman and chief executive officer. He describes himself as the carrier’s chief marketing strategist. Michael Muse calls himself better at scheduling than anyone in the business and scheduling is the most important item in the business.

Lamar Muse spends only three or four days in the office in the average week and he says his primary job is looking over people’s shoulders to be sure they don’t make any big mistakes. The only change he has made in the procedures he followed at Southwest, he adds, “is that now I personally investigate and answer all complaints. That’s the best way to spot the trouble areas.”

Muse Air is actually being run exceptionally well, his subordinates say, by Michael Muse, who is president and chief operating officer. Although he claims only three years of actual airline experience with Southwest, he has spent a lifetime absorbing airline knowledge from his father. His own formula for success for a new airline is good management, good equipment, and twice as much money as you think you need.

Senior VP-marketing, Edward W. Lang, came to Muse Air from Southwest where he was VP-personnel and earlier VP-marketing. He has been in the airline business for 24 years with Southwest, Braniff, Alaska Airlines and West Coast Airlines. He is pleased with Muse Air’s marketing efforts so far, with one exception: “We’ve done so well at projecting ourselves as a first-class airline,” he says, “that people think we are more expensive to fly than Southwest.” Future ads will give more emphasis to Muse Air’s low fares.

James T. Ferguson, VP-flight operations, had been at Texas International for 33 years, most recently as chief pilot at the Dallas base, when he left what he describes as “an unhappy airline” to join Muse Air. He recruited Muse Air’s initial corps of 19 pilots from “thousands of applicant,” and all had DC-9-30 type ratings when they were hired. In fact, Muse Air’s lowest-time copilot has more than 2,000 hours of DC-9 captain time. Five came from Midway Airlines, two from Evergreen, and several from the military. Muse Air is doing its own ground and recurrent flight training, and is contemplating purchase of a $6.5 million DC-9-80 simulator.

VP-maintenance and engineering Buford A. Minter came to Muse Air from Braniff, which he joined in 1939 when its fleet consisted of four Douglas DC-2s and four Lockheed 10s. He was staff VP-base aircraft maintenance when he departed after 42 years “because I wanted to be the top man in a maintenance operation and I couldn’t do it at Braniff.”

Minter and McDonnell Douglas have developed what he considers to be a unique maintenance program for Muse Air’s two airplanes. Required tasks have been divided into 64 packages, and a package is performed on each aircraft on alternating nights. At the end of 64 visits, everything through the C check has been accomplished and very few items have been repeated. And the workload is such that Minter thinks he can add at least one more airplane to the system without increasing his workforce of 30.

NEW HANGAR SCHEDULED

Maintenance was being done outdoors at the time of ATW’s visit, but a new hangar was scheduled for completion at the Love Field base in early September. Regular maintenance is done during a single midnight shift, but two mechanics are on duty during each of the other two shifts to take care of unexpected problems.

A firm believer that “cleanliness flights corrosion,” Minter has the airplanes washed every two weeks. Mechanics do the afterwash polishing because “it’s amazing what you see when you’re polishing.” The interiors of both airplanes receive a thorough cleaning every night.

Minter says the Super 80 has been “exceptionally reliable and easy to maintain,” and that Muse Air “often goes a whole week with no maintenance writeups.” From the pilot’s point of view, says Ferguson, the only problem has been that “the airplane is so quiet that it’s hard to taxi – from the cockpit, you can’t hear the engines at all.” Michael Muse says that Super 80 has been burning about 16% less fuel per seat than Southwest’s 118-seat Boeing 737s.

Other ex-Southwest types at Muse Air include C. Douglas Lane, VP-purchasing and stores, and controller Jim Thomson. Lane has 21 years of airline background, and has worked for Lamar Muse both at Southwest and Universal. Thomson, who was assistant treasurer at Southwest, has been in the airline business for six years.

Thomson is a believer in the Muse philosophy that “productivity is the key to profit.” When you work for Lamar Muse, he adds, “the only thing you can be sure of is that you’ll be short-handed.”

Second-level management at Muse Air includes staff VP-station operations Buck White, a former station manager for Southwest and Braniff; staff VP-sales Diane Harker, who was with American for 11 years; and staff VP-inflight services Sandra Coffin, who was at Eastern.

At the station level, says White, “cross-utilization is the name of the game.” His staff of 54 is half male and half female, “and you’ll find women working the ramp and men working the ticket counter. Moving people around cuts boredom.”

Muse currently has 220 employees, a large number of whom are called “representatives.” Its 37 “Inflight service representatives” are garbed in an ensemble of camel vest or jacket, blouse of navy “Muse Air club print,” and navy skirt with a 13 inch slit (sex is not entirely dead at Muse Air). A crimson smock is worn during inflight beverage service. Ground-based “Customer service representatives” wear camel skirt or pants with navy vests or jackets. Male ISFs wear camel blazers with navy slacks and club print ties. Pilots wear brown suits with camel braid and ecru shirts.

FLIGHT CREWS PAID PER TRIP

As is the case at Southwest, pilots and flight attendants are paid by the trip, a practice which Michael Muse says leads to high productivity. Captains receive $30 a trip, first officers $15, senior ISRs $12 and junior ISRs $11. All should be able to fly 1000 trips a year, says Michael Muse, so their starting salaries are about the same as those on any other airline.

Muse Air’s Civil Aeronautics Board certificate gives it authority to 24 cities in 13 states stretching from Texas to Pennsylvania. Its ultimate plan is to establish high-frequency, low-fare operations centering on three hubs – Houston, Atlanta and Chicago.

At the time of ATW’s visit, the carrier was finalizing plans to acquire a third DC-9-80 in November from Polaris Leasing, and was debating the best use of this aircraft. Michael Muse appeared to favor the initiation of a low-fare Hobby-Atlanta service, but Lamar Muse was leaning towards building feed for the present service by operating to the lower Rio Grande Valley.

The Valley already is served by Southwest, but Lamar Muse thinks that he himself created a chink there. While at Southwest, he launched service to Harlingen, the centermost of the Valley’s three major cities, as a means of achieving high load factors by consolidating traffic. But a large proportion of the Valley’s traffic originates or terminates in Brownsville or McAllen, he notes, and direct service to those two points could very well be profitable.

Right now, however, Muse Air’s primary problem is to build its Love-Hobby loads. And it seems to be taking a lot of cues from a handwriting expert’s analysis of its distinctive logo.

The signature, which is not that of either Lamar or Michael Muse, shows, according to the analyst, “an awareness of the past and the ability to capitalize on past experiences… confidence in the future… pride… attention to detail… loyalty.” And “any exuberance is held in check with appropriate caution and emphasis on the safety and well-being of others.”

Big Daddy puts it more simply. “We’re aiming,” says Lamar Muse, “to be known as the best little airline in Texas rather than the biggest bus service in the sky.”

The October 25, 1981 Official Airline Guide shows more than 80 weekday flights from Dallas to Houston operated by a total of eight airlines: American, Braniff International, Delta, Muse Air, Republic, Southwest, Texas International and Western.

The year 1981 ended with Muse Air’s fleet of two McDonnell Douglas MD-80 aircraft serving Dallas Love Field and Houston Hobby Airport. The company’s net loss for the year was $3.97 million.

1982

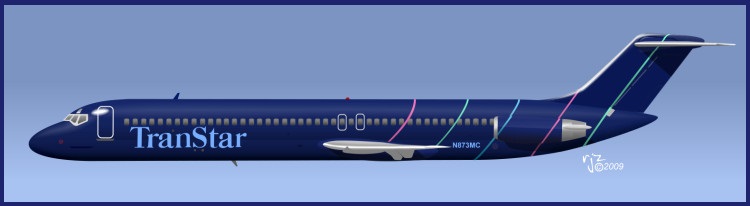

Beginning in July 1982, Muse Air began accepting delivery of six McDonnell Douglas MD-82 aircraft built specifically for the airline. One of these aircraft, N932MC, is shown departing Long Beach in the early 1980s.

With the delivery of these six aircraft, the original two MD-81s that had been built for Air Austral were returned to McDonnell Douglas in December 1982.

Photo credit: Unknown

“Muse Air Asks Tulsa to Lobby for Airline Service”

(The Daily Oklahoman – May 12, 1982) Muse Air, a fledgling Dallas-based airline which took delivery of two new jet aircraft that were to be used to expand service into Oklahoma, today will appeal to Tulsans to pressure the government to let the service begin.

Muse, headed by Lamar Muse, who earlier founded Southwest Airlines, will bring to Tulsa one of the two new planes. The purchase of the planes was financed with a $41-million loan guaranteed last year by the Federal Aviation Administration.

However, Muse won’t be able to use the McDonnell Douglas Super 80 jets to carry passengers into and out of Oklahoma.

Last February the FAA changed its rules to prohibit certain new landing “slots,” preventing Muse from starting regular flights to Tulsa. Muse isn’t giving up. The company is lobbying U.S. Transportation Secretary Drew Lewis to get the FAA to allow Muse to expand its service. As part of Muse’s lobbying efforts, lobby “kits” will be given to those to look at the Muse plane when it arrives at 1:30 p.m. at Gate 60 of Tulsa International Airport.

On May 12, 1982, Dallas/Fort Worth-based Braniff International Airways filed for bankruptcy protection and ceased operations. As a result, on May 14, Muse Air was granted emergency authority to begin serving both Midland/Odessa and Tulsa despite ongoing restrictions still in place due to the Air Traffic Controllers’ strike.

Muse Air service to both cities would begin two days later on May 16, 1982.

Muse Air’s May 16, 1982 timetable shows the addition of Midland/Odessa and Tulsa route system. Both of these cities were linked to Dallas Love with six weekday roundtrips and slightly reduced frequencies on weekends.

With the addition of the new cities, Muse Air was now operating 25 weekday departures from Love Field.

The May 16, 1982 timetable also includes planned schedules for Austin and San Antonio set to begin in July 1982 subject to Federal Aviation Administration approval.

However, with continued FAA airspace restrictions in effect due to the ongoing Air Traffic Controllers’ strike, service to those two cities was postponed.

Muse Air’s September 15, 1982 timetable includes the introduction of service to Los Angeles beginning October 1.

The initial Los Angeles schedule consisted of three daily nonstop flights to Houston Hobby (reduced to two flights on Sunday). Muse Air originally used Gate 44 in Terminal 4 at Los Angles International Airport.

Initial Los Angeles schedule:

| From | To | Flight | Depart | Arrive | Frequency |

| HOU | LAX | MC 860 | 8:45am | 10:00am | ExSun |

| HOU | LAX | MC 862 | 12:45pm | 2:00pm | Daily |

| HOU | LAX | MC 864 | 4:45pm | 6:00pm | Daily |

| LAX | HOU | MC 861 | 7:15am | 12:20pm | ExSun |

| LAX | HOU | MC 863 | 10:50am | 3:55pm | Daily |

| LAX | HOU | MC 865 | 2:50pm | 7:55pm | Daily |

Muse Air fares effective September 15, 1982:

“Colorful Celebration Welcomes Muse”

(Muse Air Club Musings – November/December 1982) Muse Air began non-stop service between Houston Hobby and Los Angeles International on October 1, offering three round trips daily at one low rate of $130 one way.

The inauguration of the new route featured a colorful celebration at the McDonnell Douglas aircraft plant in Long Beach where Muse Air took delivery of two more Super 80 aircraft. This brings the Muse fleet to six.

Attending the ceremony was television and movie personality Dennis Cole who was particularly impressed with Muse Air’s policy banning smoking on all flights. Mr. Cole is honorary chairman of the Great American Smoke Out sponsored by the American Cancer Society.

Flights depart from Houston Hobby for Los Angeles at 8:45am, 12:45pm and 4:45pm Central Standard Time. Departure times from Los Angeles International to Houston are 7:15am, 10:50am and 2:50pm Pacific Standard Time.

Photo credit: Unknown

“Fasten Your Seat Belts”

“The battle between Muse Air and Southwest is only beginning.”

(Peter Applebome, Texas Monthly – November 1982) If you watch television in Houston, Dallas, Midland-Odessa, or Tulsa, you have probably noticed two sets of commercials for two particular airlines. One set shows plain, ordinary folks saying how nice it is to fly fifteen-month-old Muse Air – how swell the service is and how different the classy planes are from the “cattle cars” the other guy offers. The second set shows other plain, ordinary folks saying how much their appreciate their trusty old friend Southwest Airlines – how cheap and convenient the flights are, how nice it is to be able to fly to both Houston airports, and how much fun it is to choose your own seat and make friend on the plane.

Southwest long ago outgrew its scrappy-new-kid-on-the-block persona. From its meager start in 1971, when it began flying between Houston, Dallas and San Antonio, it has come to dominate the Southwest with flights to nineteen cities, nine of them outside Texas. In the process, it has seen its rival Texas International virtually abandon the regional market and its archenemy Braniff die a prolonged and messy death. Now, for the first time, Southwest is facing the perils of being number one. Having beaten the stuffing out of the big, bulky, high-cost trunk carriers, it’s suddenly faced with a competitor on its own turf, one that is trying to improve on the cut-rate fare formula Southwest used to turn itself into the brightest star of the airline industry. The seeds of the conflict were sown in 1978 when Lamar Muse failed in a power play at Southwest and was replaced as president by Herbert Kelleher. Muse and his son, Michael, founded Muse Air early last year with flights between – shades of Southwest – Houston and Dallas.

For a long time, there was doubt that this particular episode of “Fear at 30,000 Feet” would ever come off. Muse Air, after all, has gone through just about the stormiest debut ever weathered by an airline, with the possible exception of Southwest’s. Muse had been flying for just nineteen days when the air traffic controllers went on strike. The strike led the Federal Aviation Administration to restrict access to new landing slots, in effect leaving Muse with no place to fly. The company’s future looked so dim last summer that its stock plunged from an opening price of $17.50 a share to a low of $3.50. One analyst even put Muse on a special “watch list” along with the likes of Pan Am and Braniff. Lamar Muse began going around saying things like “We’re not dead, but we’ve got one foot in the grave.” Meanwhile, Southwest was chalking up a 16 percent operating profit margin, the highest in the industry.

Then Braniff’s demise helped open up the slots Muse needed to survive, and Muse devised a makeshift route structure to get its planes in the air. It had enough cash to weather a $7 million loss in 1981 and the first six months of 1982, and it finally broke into the black for the third quarter of this year. It took the sale of tax credits to do it, but Muse now shows a $645,000 profit for the year.

This fall, Southwest announced a $10 discount on round-trip tickets in the markets where it competes with Muse. At the same time, it raised fares on most of the routes serve or doesn’t have an interest in. Ghosts of air wars past began to haunt the folks at Muse Air headquarters in Dallas. “We’re exactly in the same spot today that Southwest was in with Braniff in February 1973,” says Lamar. “We have lost a lot of money, and Kelleher things he has us on the ropes just as Braniff thought it had Southwest on the ropes. He’s doing exactly what Harding Lawrence or Braniff did in 1973.”

There probably isn’t another industry in Texas – oil included – in which the players are so well known and such a premium is placed on entrepreneurial razzle-dazzle. And no one has ever accused Lamar Muse of being a shrinking violet. One of the biggest reasons his airline has made it this far has been Lamar’s ability to get his case before the public. So it may be advisable to take his Southwest-Braniff analogy with a grain of salt. After all, Southwest is only offering a $10 discount; in 1973 Braniff doubled its flights and halved its fares in an attempt to gut Southwest. “Muse had a round-trip discount of $10 from March until September fifteenth,” says Kelleher. “All we’re doing is adopting their own fare structure. That might not be enormously creative, but it hardly constitutes an onslaught or unfair competition or oppression.” Southwest may have played hardball by trying to prevent Muse from obtaining the landing slots it needed, but its tactics don’t compare to Braniff’s.

There are other differences as well. Southwest ushered in the era of cut-rate fares and increased the total traffic between Houston and Dallas by almost 50 percent the first year it was in business. Muse, with its sleek McDonnell Douglas Super 80s and reserved seating, is selling better service, not lower fares.

None of which means Muse will have an easy time of it. What Muse is attempting is in some ways much tougher than what Southwest did. When Southwest took on Braniff, it was facing an airline with a 54 percent on-time performance. When Muse started, Southwest had a 92 percent on-time rating. Muse is challenging a successful low-cost carrier on its own turf. No one has done that successfully, and some airline analysts doubt that it’s possible. On the other hand, Southwest is not impregnable. To some degree, it’s a prisoner of its own success. By becoming a form of mass transit – Texas’ Long Island Railroad – it has become big and erratic enough to be resented. It’s safe to say air travelers don’t have the same unalloyed affection for Southwest that some Wall Street analysts do. Nor did the airline help itself by flying planes between Dallas and Houston that were 80 percent full (the industry average is 60 percent). That indicated to Muse that there was room for a competitor.

In fact, measured only on the basis of the routes both airlines fly, Muse is doing remarkably well. For instance, of the passengers who board at Hobby and deplane at Love or vice versa (and not the ones who travel that segment as part of a longer Southwest flight), about 44 percent fly on Muse. Muse also claims to carry 38 percent of the Midland traffic and 45 percent of the Tulsa traffic. Such numbers don’t tell the whole story, but they do suggest Muse can compete with Southwest.

Muse’s long-term future does not depend on winning a dogfight with Southwest. Even Lamar admits the airline’s original strategy was to go head-to-head with Southwest only in markets where there was clearly room for a competitor. Lamar Muse still wants to add service to Austin, San Antonio and perhaps the Valley. But the company’s real future, assuming that the FAA stops rationing slots sometime next year, is to fly to cities like Chicago, Detroit, Cincinnati and Saint Louis, to head east from Texas as Southwest heads west. Those are the routes Muse’s planes are designed to serve and the ones were it can take on long-haul carriers, such as Continental, Eastern, Delta, and Pan Am, which are more vulnerable than Southwest.

It looks as if deregulation just may work after all. In the seventies, airlines like Southwest and Pacific Southwest in California prospered because they circumvented federal route restrictions by only flying intrastate. In the deregulated eighties, Muse could emerge as a prototype of a new generation of carriers, one that will be able to challenge both the Southwests and the Easterns. “What this was supposed to be about was competition,” says Michael Muse. “You’re not going to have monopolies anymore. It’s not just American and Delta that are going to have to compete. It’s Southwest and Pacific Southwest as well.”

Muse Air boards its one millionth passenger on December 26, 1982 and ends the year with a net profit of $11.46 million as a result of the sale of tax credit on three aircraft.

1983

Muse Air’s January 1, 1983 timetable shows the addition of two new routes: Midland/Odessa to both Houston Hobby and Los Angeles.

Muse Air’s fleet of six MD-80s was now operating 62 weekday flights between six city pairs:

Dallas Love Field-Houston Hobby: 14 weekday flights

Dallas Love Field-Midland/Odessa: 7 weekday flights

Dallas Love Field-Tulsa: 6 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Dallas Love Field: 14 weekday fights

Houston Hobby-Los Angeles: 2 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Midland/Odessa: 1 weekday flight

Los Angeles-Houston Hobby: 2 weekday flights

Los Angeles-Midland/Odessa: 1 weekday flight

Midland/Odessa-Dallas Love Field: 7 weekday flights

Midland/Odessa-Houston Hobby: 1 weekday flight

Midland/Odessa-Los Angeles: 1 weekday flight

Tulsa-Dallas Love Field: 6 weekday flights

Photo credit: Unknown

Muse Air’s April 24, 1983 timetable shows that service between Dallas Love Field and Houston Hobby Airport had been expanded to hourly. Weekday flights between the two cities increased from 14 to 17.

This timetable also has a terminal map of Los Angeles International Airport and Muse Air’s location at the airport. Included in the map is Terminal 1. Still under construction at the time, Terminal 1 would be the future home for Muse Air at LAX.

Muse Air’s July 1, 1983 timetable announced the introduction of upcoming service to the airline’s sixth destination: Lubbock.

Lubbock service would begin on August 7 with six weekday roundtrip flights from Dallas Love Field.

Photo credit: Russell Goutierez via Museair.com

In July 1983, Muse Air began operating a single McDonnell Douglas DC-9-30 configured with 110 seats. The aircraft, registered N502MD, had originally been operated by Martinair Holland. Muse Air added the aircraft to its fleet when the deliveries of several larger DC-9-50s being acquired from Swissair were delayed. The aircraft left the fleet early the following year.

“Muse Finally Taking Off After Struggle”

(Associated Press – July 17, 1983) The drinks are free, the are soft leather and the state-of-the-art aircraft is painted in a subtle cream color on Muse Air. But when the line’s founder, Mike Muse, said he wanted to create a sophisticated airline, his flamboyant father told him he was crazy.

Muse’s father Lamar knows something of airlines himself. As president of Southwest Airlines in the early 1970s, he put its stewardesses in hot pants, painted his planes bright red and orange, promised his passengers “love in the sky,” and turned the fledging commuter carrier into one of the nation’s most profitable.

Mike Muse’s gamble, Muse Air, turned 2 years old Friday. He said it is poised for its widest expansion to date and is showing its first real profits.

The future didn’t always look so bright for Mike Muse, a 30-year-old who says Braniff International, a longtime rival of his father’s, indirectly helped his dreams take flight.

The first Muse Air DC-9 Super 80 took off July 15, 1981, and 23 days late the air traffic controllers walked out on strike. The Federal Aviation Administration immediately began rationing landing rights at the nation’s major airports, so Muse was left with nowhere but Houston to fly to.

Southwest, led by Lamar Muse, had battled with Braniff in 1971 for the lucrative Dallas-to-Houston route. Southwest survived, but Braniff was eventually grounded by its $1 billion debt in May 1982.

Muse Air picked up some Braniff landing slots and opened routes.

Mike Muse had worked two years at Southwest, his only full-time industry experience, when he and his father were fired in 1978.

An accountant, Mike Muse got a job with Price Waterhouse and Co.

He first approached his father with the idea of a new airline in January 1980: “I had to drag Lamar in kicking and screaming… I needed his experience. He knew what a tough row to hoe is was.”

The elder Muse questioned his son’s sanity, but said, “It takes a crazy man to be an entrepreneur.”

Together, they raised $30 million in cash. Mike Muse became president; Lamar Muse, chairman of the board and chief executive officer, a title he relinquished to his son a year ago.

The father-son team immediately departed from some of the brash ideas that had been so successful at Southwest.

Where Southwest started out brassy and faddish, Muse Air has aimed to be chic and sophisticated, Mike Muse said. Smoking is banned on Muse Air flights; the leather seats, assigned. Drinks are free. The inflight magazine is Texas’ slick upscale Ultra.

“It was not a hot pants market anymore,” he said. “Dallas and Houston are more cosmopolitan now.”

Muse Air had a net profit of $11.5 million last year despite an operating loss of $4.7 million, because of the sale of some tax credits. But the airline has turned an operating profit for two straight months, and its load factor, a measure of how full the flights are, has finally risen above 50 percent.

Muse begins flying to its sixth destination, Lubbock, on August 7 and plans to begin service to Austin and San Antonio within a year.

Muse Air’s August 7, 1983 timetable includes the company’s new service between Lubbock and Dallas with six weekday roundtrip flights.

The timetable also announced additional upcoming Lubbock service. Beginning September 11, 1983, Muse Air would expand its presence in Lubbock to include one daily roundtrip to both Houston Hobby Airport and Los Angeles.

Photo source: Museair.com

Muse Air’s September 11, 1983 timetable includes the company’s new routes between Lubbock and Houston Hobby and Lubbock and Los Angeles.

The timetable also shows upcoming new service between Houston Hobby and Tulsa as well as new service to Austin with flights to Dallas Love Field and Houston Hobby beginning in November.

In October 1983, Muse Air began taking delivery of the smaller McDonnell Douglas DC-9-50 aircraft. The DC-9-50s were initially configured with 130 seats compared to 155 on the larger MD-80s. Muse Air would eventually acquire eight of the aircraft.

Muse Air’s November 13, 1983 timetable includes the airline’s new Austin service.

The initial Austin schedule consisted of eight weekday flights to Dallas Love Field, three weekday flights to Houston Hobby Airport and one weekday flight to Los Angeles with reduced frequencies on weekends.

Also included in this timetable was an advertisement for Muse Air’s new Concourse C at Hobby Airport. Construction of the new $3 million concourse had begun on April 11 and Muse Air began operating out of the new facilities on November 13.

Muse Air fares effective November 13, 1983:

Photo source: Museair.com

Muse Air ended 1983 with a fleet of nine aircraft serving seven cities. Net loss for the year was $1.96 million.

1984

Muse Air’s February 5, 1984 timetable shows that New Orleans and Ontario, California had been added to the route system.

New Orleans service was launched with five weekday roundtrips to Houston Hobby (four on Saturdays).

New service to Ontario consisted of flights to both Houston Hobby and Los Angeles with most flights linking each of the three cities.

Initial Ontario flight schedules were:

| Flight | From | To | Depart | Arrive | Frequency |

| MC 861 | HOU | MAF | 7:15am | 8:30am | ExSun |

| MC 861 | MAF | LAX | 8:45am | 9:15am | ExSun |

| MC 861 | LAX | ONT | 9:45am | 10:15am | ExSun |

| MC 862 | ONT | HOU | 10:45am | 3:30pm | Daily |

| MC 867 | HOU | ONT | 4:15pm | 5:15pm | Daily |

| MC 867 | ONT | LAX | 5:30pm | 6:00pm | SatOnly |

| MC 868 | ONT | LAX | 5:30pm | 6:00pm | ExSat |

| MC 868 | LAX | HOU | 6:30pm | 11:30pm | ExSat |

| MC 869 | HOU | ONT | 9:00pm | 10:00pm | ExSat |

| MC 869 | ONT | LAX | 10:30pm | 11:00pm | ExSat |

Muse Air’s February 5, 1984 timetable also shows that the following routes had been discontinued:

• Houston Hobby-Lubbock

• Houston Hobby-Tulsa

• Los Angeles-Lubbock

Additionally, this timetable is the first to publish schedules to seven additional cities served in the west by Newport Beach, California-based AirCal via connections from Muse Air flights at Los Angeles and Ontario.

Muse Air and AirCal had launched this multi-state marketing program in December 1983 and it included joint fares, coordinated baggage handling and cooperative sales efforts.

A diagram of airport facilities in several Muse Air cities shows that the airline had relocated to the brand-new Terminal One at Los Angeles International Airport. The new terminal had opened on January 23.

Photo credit: Frank C. Duarte, Jr.

Muse Air had announced intentions to begin flying to Little Rock beginning on April 29, 1984. On February 21, the company announced that it was moving up the start date of Little Rock service to March 1. However, just days later, on February 27, Muse Air announced it was abandoning all plans to serve Little Rock after Southwest Airlines announced it would also be entering the Dallas-Little Rock market offering $10 one-way fares.

Muse Air’s March 1, 1984 timetable shows that service to Lubbock has been discontinued and that the airline had added 4 weekday nonstops between Dallas Love Field and New Orleans.

Muse Air was now operating 106 weekday flights serving 8 cities:

Austin-Dallas Love Field: 7 weekday flights

Austin-Houston Hobby: 3 weekday flights

Austin-Los Angeles: 2 weekday flights

Dallas Love Field-Austin: 8 weekday flights

Dallas Love Field-Houston Hobby: 16 weekday flights

Dallas Love Field-Midland/Odessa: 5 weekday flights

Dallas Love Field-New Orleans: 4 weekday flights

Dallas Love Field-Tulsa: 5 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Austin: 2 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Dallas Love Field: 17 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Midland/Odessa: 1 weekday flight

Houston Hobby-New Orleans: 5 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Ontario: 2 weekday flights

Los Angeles-Austin: 2 weekday flights

Los Angeles-Houston Hobby: 1 weekday flight

Los Angeles-Midland/Odessa: 1 weekday flight

Los Angeles-Ontario: 1 weekday flight

Midland/Odessa-Dallas Love Field: 5 weekday flights

Midland/Odessa-Houston Hobby: 1 weekday flight

Midland/Odessa-Los Angeles: 1 weekday flight

New Orleans-Dallas Love Field: 4 weekday flights

New Orleans-Houston Hobby: 5 weekday flights

Ontario-Houston Hobby: 1 weekday flight

Ontario-Los Angeles: 2 weekday flights

Tulsa-Dallas Love Field: 5 weekday flights

Photo credit: Frank C. Duarte, Jr.

Muse Air’s April 29, 1984 timetable shows the introduction of new service to Las Vegas.

Initial Las Vegas service consisted of one daily flight to both Houston Hobby Airport and Ontario.

Initial Las Vegas schedule:

| From | To | Flight | Depart | Arrive | Frequency |

| ONT | LAS | MC 866 | 11:15am | 12:05pm | Daily |

| LAS | HOU | MC 866 | 12:30pm | 5:15pm | Daily |

| HOU | LAS | MC 871 | 7:30pm | 8:30pm | Daily |

| LAS | ONT | MC 871 | 9:00pm | 9:50pm | Daily |

Photo source: texashistory.unt.edu via Museair.com

Photo source: texashistory.unt.edu via Museair.com

Photo source: texashistory.unt.edu via Museair.com

Photo source: texashistory.unt.edu via Museair.com

Photo source: texashistory.unt.edu via Museair.com

Photo source: texashistory.unt.edu via Museair.com

Muse Air’s July 15, 1984 timetable shows that the airline had discontinued its nonstop service between Midland/Odessa and Los Angeles.

“Who’s In Charge at Muse Air?”

(Texas Monthly “Low Talk”, August 1984) Who’s in charge at Muse Air? Not Big Daddy, Lamar Muse. Lamar, the founder of Southwest Airlines, was the high-profile figure when Muse began three years ago. And though his son Michael is president, Muse onlookers have assumed that Lamar, who stepped down as chairman but continues to serve on the board, still calls many of the shots. Actually, son regularly overrules father to the point that Lamar is barel a factor. One Dallas investment banker, Shad Rowe of Rowe and Company, wrote an angry letter to the Muse Air board, charging that the company raised $60 million in the public market solely on the strength of Lamar’s track record and that the management had breached the stockholders’ trust.

Photo credit: Russell Goutierez via Museair.com

“Muse Air Gets New President”

(The New York Times – September 27, 1984) Sam Coats has been named president and chief operating officer at the Muse Air Corporation, the company said yesterday.

He succeeds Michael L. Muse, who continues as the airline’s chairman and chief executive officer. Mr. Coats, who was also elected to Muse Air’s board of directors, most recently served as a vice president at the Southwest Airlines Company.

Before joining Southwest, Mr. Coats, who is 43 years old, held senior management positions with Texas International Airlines (now Continental) and Braniff International. An attorney, in 1971-72 he served as a state representative from Dallas County.

Based in Dallas and founded in 1980, Muse Air offers scheduled low-fare airline service to nine cities, primarily in the Southwest, with most flights connecting to Dallas or Houston. Service was recently expanded to include Las Vegas and New Orleans.

Muse Air’s October 28, 1984 timetable shows that service to Ontario had been discontinued.

However, San Jose was added to the route system with two weekday nonstops to Las Vegas with continuing service to either Austin or Houston.

Other new routes in this timetable included Las Vegas-Austin, Las Vegas-Los Angeles and Las Vegas-Midland/Odessa.

With this timetable, Muse Air was operating 105 weekday flights to 9 cities:

Austin-Dallas Love Field: 6 weekday flights

Austin-Houston Hobby: 4 weekday flights

Austin-Las Vegas: 1 weekday flight

Austin-Los Angeles: 1 weekday flight

Dallas Love Field-Austin: 6 weekday flights

Dallas Love Field-Houston Hobby: 14 weekday flights

Dallas Love Field-Midland/Odessa: 4 weekday flights

Dallas Love Field-New Orleans: 1 weekday flight

Dallas Love Field-Tulsa: 4 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Austin: 4 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Dallas Love Field: 14 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Las Vegas: 2 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Los Angeles: 4 weekday flights

Houston Hobby-Midland/Odessa: 1 weekday flight

Houston Hobby-New Orleans: 6 weekday flights

Las Vegas-Austin: 1 weekday flight

Las Vegas-Houston Hobby: 2 weekday flights

Las Vegas-Los Angeles: 1 weekday flight

Las Vegas-Midland/Odessa: 1 weekday flight

Las Vegas-San Jose: 2 weekday flights

Los Angeles-Austin: 1 weekday flight

Los Angeles-Houston Hobby: 4 weekday flights

Los Angeles-Las Vegas: 1 weekday flight

Midland/Odessa-Dallas Love Field: 4 weekday flights

Midland/Odessa-Houston Hobby: 1 weekday flight

Midland/Odessa-Las Vegas: 1 weekday flight

New Orleans-Dallas Love Field: 1 weekday flight

New Orleans-Houston Hobby: 6 weekday flights

San Jose-Las Vegas: 2 weekday flights

Tulsa-Dallas Love Field: 5 weekday flights

A postcard showing Houston Hobby Airport circa 1984. In addition to multiple Muse Air jets, also visible are an Air One Boeing 727, two American Airlines Boeing 727s, a Frontier Airlines Boeing 737, a Pan Am 727, two Republic Airlines DC-9s and multiple Southwest Airlines Boeing 727s and 737s. (Photo credit: R.A. Young)

Muse Air ended 1984 with a net loss of $17.042 million.

1985

Muse Air’s January 15, 1985 timetable shows the addition of both Brownsville and McAllen to the route system.

The new cities were served six times daily with each flight operating Houston-Brownsville-McAllen-Houston or vice versa. (The timetable shows scheduled flight times between the two south Texas cities to be 20 minutes.)

Additionally, the timetable indicates new nonstop service between Austin and Midland/Odessa (one daily roundtrip) while nonstop service between Dallas Love Field and New Orleans had been discontinued.

“Texan’s Bid to Save Muse Air”

(Agis Salpukas, The New York Times – January 19, 1985) M. Lamar Muse, who has spent 36 of his 64 years in the airline business, says he would like nothing better than to call it quits, and spend the rest of his life in his condominium in Austin, Tex., and at his summer home in Vancouver, British Columbia, where he can fish for salmon.

”I’d rather be doing that than sitting in hot Dallas this summer trying to make this airline work,” the garrulous executive said.

Yet, he added, he has little choice but to try to save Dallas-based Muse Air, founded by his son, Michael L. Muse. The airline, which is in a dogfight with rival Southwest Airlines, has never made a go of its flight operations – its profits to date are the result of tax credits. In the first nine months of 1984, Muse Air lost $9.3 million.

A Recent Crisis

The elder Mr. Muse, who, despite his reluctant unretirement, has his own reasons for relishing a fight with the bigger Southwest Air, staved off a recent crisis in December only through the intervention of a friend, Harold C. Simmons, chairman of the Amalgamated Sugar Company, who pumped $16 million into the carrier.

In return for the $16 million, however, Mr. Simmons wanted his friend, whom he described as ”unusually capable and intuitive in marketing and scheduling an airline, and running the whole thing,” to again take over as chairman of the airline, a post he had turned over to son last May. So Lamar Muse took the reins Dec. 18.

Mr. Simmons, who will also get 2 million shares of new convertible preferred stock, estimated that the airline’s fleet of six McDonnell Douglas Corporation MD-80 aircraft and five DC-9-50 planes – and Muse’s valuable gates at various airports – are worth far in excess of his investment.

Bitter Fare Wars

During his long aviation career, Mr. Muse has become somewhat of a legend in Texas aviation. He began his career in 1948 when he joined Trans Texas Airways as treasurer. But it was as chief executive of Southwest Airlines from 1971 t0 1978 that he earned his reputation as a crafty executive, engaging in bitter fare and route wars with rivals Braniff and Texas International.

He made Southwest, whose main route was between Love Field in Dallas and Hobby Airport in Houston, into a profitable ”love airline” – complete with miniskirted stewardesses and bare-bones fares. He even gave away bottles of Chivas Regal to full-fare customers.

But in March 1978 Mr. Muse made a gross miscalcuation. He asked the Southwest board to choose between himself and one of the airline’s founders, Rollin King. The board was stunned, and returned the favor by ousting a shocked Mr. Muse.

So Mr. Muse bought himself a Yamaha and tore down Texas highways. He also bought a small trucking company, and learned to drive an 18-wheeler rig.

But Michael Muse, 35, who had lost his job as a counsel at Southwest when his father was shown the door, dreamed of getting back into the airline business. On Jan. 30, 1980, he incorporated Muse Air, and floated a public stock offering in April 1981.

The airline began operations in July with 28 flights daily between Dallas and Houston, a market dominated by Southwest Airlines. Muse then had a fleet of two DC-9-80’s.

‘Why Kill Yourself?’

The elder Mr. Muse, who was asked to become chairman of the board by his son, did so reluctantly. The year 1981 was one of heavy losses for airlines. He recalled he told his son: ”There are so many easy ways to make money. Why kill yourself with an airline?”

Michael Muse, now vice chairman, said the reason he began to fly from Houston to Dallas against such a formidable competitor was that existing carriers could not handle all the traffic. But that first year, when the strike by the air controllers prevented Muse from expanding, it lost $3.91 million.

In 1982 the airline went on a major expansion. It sold more stock and bought six MD-80’s and began flying into Midland and Odessa, Tex.; Tulsa, Okla., and Los Angeles. That year, the airline earned $11.5 million – solely from the sale of tax credits for plane purchases.

Even though the route structure and number of passengers grew, the airline started losing money. Its stock price on the American Stock Exchange has slumped from a 52-week high of 15 1/8 to the current 5 3/8.

Hans Plickert, an analyst for E.F. Hutton & Company, said that with the elder Mr. Muse – whom he described as a genuis at scheduling and finding market miches – at the controls, Muse has a fighting chance. Mr. Plickert said that Michael Muse sought to compete directly with the stronger Southwest Airlines on too many routes. ”He was trying to prove that he was better than Southwest,” he said. Southwest has a fleet of 54 planes, and Muse has 11.

Michael Muse said there was nothing wrong with the strategy of providing a better class of service than Southwest, at matching or slightly higher fares. Muse has leather seats that provide more legroom. Seats are assigned – on Southwest most seats are on a first-come, first-served basis – and smoking is not permitted anywhere on a Muse plane.

”It’s the competitive environment we’re in” he said. ”When you have a competitor that is willing to cut its yield so low, to levels some people might call predatory, then it’s hard to make a buck.” He noted that in Muse’s market from Houston to Los Angeles, where it was charging $120 one way, Southwest eventually cut one-way fares to $80. That hurt, since the route represented 35 percent of Muse’s revenue miles.

A $10 Fare

And when Muse announced it would start service to Little Rock, Ark., in January, Southwest bought up the available airport facilities and offered an introductory fare of $10 one way, which later went up to $47. Muse decided to stay out of the market.

Lamar Muse has taken some quick steps to attract more customers. He has rescheduled the flights between Dallas and Houston so that they all leave – shuttle-like – at 45 minutes past the hour. Mr. Muse has also inaugurated service to McAllen and Brownsville, Tex., from Dallas and Houston – a move that will mean that customers from those cities will no longer have to drive an hour to the airport in Harlingen, where Southwest and American have flights.

But he acknowledged that it would be difficult to turn Muse around. The airline has a monthly interest charge of $1.47 million to meet, and its debt is $180.8 million. ”I’m certain we can improve the situation,” Mr. Muse said. ”It’s nice to make a profit, but I can’t guarantee that for ’85.”

After beginning work at about 8 A.M., he usually takes a 7:45 P.M. flight back to Austin. ”Since I’m in it,” Mr. Muse said, ”the blood is beginning to flow. I’m beginning to enjoy it. It’s exciting.”

“Southwest Signs Pact to Buy Muse Air”

(Associated Press – March 11, 1985) Southwest Airlines said Monday it agreed to buy ailing rival Muse Air Corp. for cash and stock valued at more than $60 million.

Southwest said Muse would continue operating as a separate airline under its current name, and would retain its current workers. Both Muse and Southwest are based at Dallas’ Love Field.

Muse’s chairman and founder, M. Lamar Muse, would become vice chairman of Southwest’s new subsidiary, and the acquisition is subject to approval by Muse’s shareholders and the U.S. Transportation Department, Southwest said.

Under the agreement, Southwest said each of Muse’s 4.64 million common shares would be exchanged for $6 cash, 0.125 share of Southwest common stock and 0.125 of a five-year warrant to buy one Southwest share for $35.

Southwest’s common stock closed Friday at $24.121/2 a share on the New York Stock Exchange. Muse closed at $8.621/2 a share on the American Stock Exchange.

All of Muse’s 2 million preferred shares are owned by Almalgamated Sugar Co., which is controlled by Dallas investor Harold C. Simmons and which provided Muse with a $16 million infusion earlier this year.

Southwest said it would purchase each preferred share for $6 in cash plus accrued and unpaid dividends, 0.125 share of Southwest common stock and 0.25 of the warrant to buy one Southwest share.

Muse, which bans smoking on its flights, never recorded an annual operating profit since it was founded four years ago. In 1984, Muse lost $17 million on revenue of $101 million.

Muse primarily serves the southwest United States, and the profitable Southwest Airlines is its main competitor.

Muse Air was founded by Lamar Muse and his son Michael after the elder Muse left Southwest in 1978, where he had been president and chief executive since 1971, when that carrier was founded.

Lamar Muse retired from Muse Air last May. Muse Air than ran into severe financial trouble before it was able to secure the financing from Simmons. However, the investment was conditioned on Lamar Muse’s return as Muse Air’s chairman and chief executive, succeeding his son.

While some scheduling changes may be made to take advantage of the medium- and long-range jets in Muse’s fleet, Muse will continue offering the same type of service it offers now, Southwest said.

Southwest Chairman Herbert D. Kelleher, in a letter to his employees, said the merger would help both airlines and he asked for cooperation.

″This proposed acquisition is in the best interests of the shareholders and employees of both carriers, and I hope that each of you will express to the Muse Air employees your delight that we are going to be working together rather than against each other in the future,″ Kelleher said.

Southwest serves 24 cities in 10 states – California, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Louisiana, Missouri, Illinois, Arkansas, Nevada and Texas. Southwest earned $49.7 million in 1984 on revenue of $535.9 million.

Muse serves 10 cities from Dallas – San Jose and Los Angeles in California; Las Vegas, Nev.; Tulsa, Okla.; New Orleans; and Houston, Austin, Brownsville, Midland-Odessa and McAllen in Texas.

“Southwest and Muse Announce Merger Agreement”